Introduction

Trunk-Based Development is not a new branching model. The word ‘trunk’ is referent to the concept of a growing tree, where the fattest and longest span is the trunk, not the branches that radiate from it and are of more limited length. It has been a lesser known branching model of choice since the mid-nineties and considered tactically since the eighties. The largest of development organizations, like Google (as mentioned) and Facebook practice it at scale. Over 30 years different advances to source-control technologies and related tools/techniques have made Trunk-Based Development more (and occasionally less) prevalent, but it has been a branching model that many have stuck with through the years.

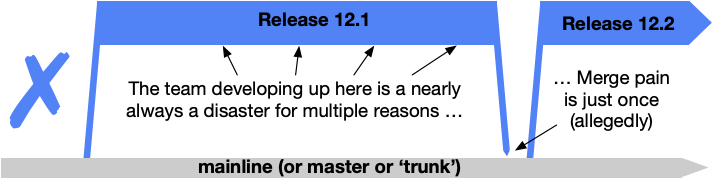

Shared branches off mainline/main/trunk are bad at any release cadence:

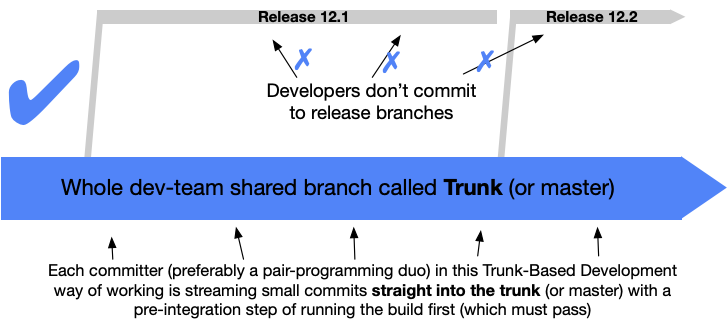

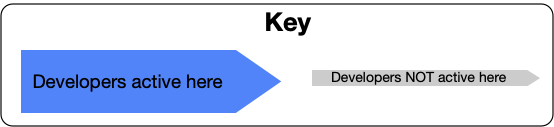

Trunk-Based Development For Smaller Teams:

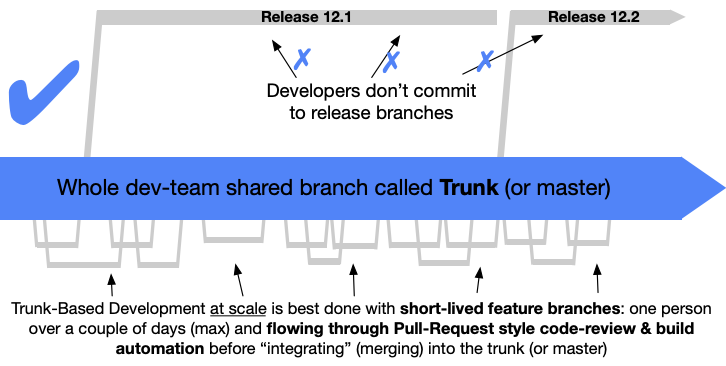

Scaled Trunk-Based Development:

Elaboration, Claims and Caveats:

Trunk-Based Development is a key enabler of Continuous Integration and by extension Continuous Delivery . When individuals on a team are committing their changes to the trunk multiple times a day it becomes easy to satisfy the core requirement of Continuous Integration that all team members commit to trunk at least once every 24 hours. This ensures the codebase is always releasable on demand and helps to make Continuous Delivery a reality.

The dividing line between small team Trunk-Based Development and scaled Trunk-Based Development is a subject to team size and commit rate consideration. The precise moment a dev team is no longer “small” and has transitioned to “scaled” is subject to practitioner debate. Regardless, teams perform a full “pre integrate” build (compile, unit tests, integration tests) on their dev workstations before committing/pushing for others (or bots) to see.

Claims

- You should do Trunk-Based Development instead of GitFlow and other branching models that feature multiple long-running branches

- You can either do a direct to trunk commit/push (v small teams) or a Pull-Request workflow as long as those feature branches are short-lived and the product of a single person.

Caveats

- Depending on the team size, and the rate of commits, short-lived feature branches

are used for code-review and build checking (CI), but not artifact creation or publication, to happen before commits land in the trunk for other developers to depend on. Such branches allow developers to engage in eager and continuous code review of contributions before their code is integrated into the trunk. Very small teams may commit direct to the trunk. - Depending on the intended release cadence, there may be release branches that are cut from the trunk on a just-in-time basis, are ‘hardened’ before a release (without that being a team activity), and those branches are deleted some time after release. Alternatively, there may also be no release branches if the team is releasing from Trunk , and choosing a “fix forward” strategy for bug fixes. Releasing from trunk is also for high-throughput teams, too.

- Teams should become adept with the related branch by abstraction technique for longer to achieve changes, and use feature flags in day to day development to allow for hedging on the order of releases (and other good things - see concurrent development of consecutive releases)

- If you have more than a couple of developers on the project, you are going to need to hook up a build server to verify that their commits have not broken the build after they land in the trunk, and also when they are ready to be merged back into the trunk from a short-lived feature branch.

- Development teams can casually flex up or down in size (in the trunk) without affecting throughput or quality. Proof? Google does Trunk-Based Development and have 35000 developers and QA automators in that single monorepo trunk, that in their case can expand or contract to suit the developer in question.

- People who practice the GitHub-flow branching model will feel that this is quite similar, but there is one small difference around where to release from.

- People who practice the Gitflow branching model will find this very different, as will many developers used to the popular ClearCase, Subversion, Perforce, StarTeam, VCS branching models of the past.

- Many publications promote Trunk-Based Development as we describe it here. Those include the best-selling ‘Continuous Delivery’ and ‘DevOps Handbook’. This should not even be controversial anymore!

One line summary

A source-control branching model, where developers collaborate on code in a single branch called ‘trunk’ *, resist any pressure to create other long-lived development branches by employing documented techniques. They therefore avoid merge hell, do not break the build, and live happily ever after.